Płock Art Gallery, Płock, Poland, Horizon of significant events – exhibition of painting

THE BARE EXPERIENCE

I get the impression that Jacek Świgulski’s art revolves around something simple, yet hard to capture. It is about the human need to give meaning to one’s experience. It sounds innocent. Unfortunately, meaning has a sad tendency to wear out. In a way, it is a price we pay for efficiency. We learn not to notice what we already know, e.g. to get to work: marveling at the light on frost-covered grass may be demotivating. If we break the routine, it is usually in favor of preplanned attractions. Thus, we are mentally stuck in a rut: everyday life is what it is and you admire what you are supposed to. We no longer seem to be able to let our thoughts wander. We can no longer afford the luxury of becoming mesmerized. Only a tiny bit of freedom, a slip road off the thought-perception mental highway towards much slower and less comfortable rough terrain, makes it possible to renew meaning and ask basic existential questions. And that is, I believe, what Świgulski seeks with his art.

While his works form a number of separate series, they all share a universal theme: “I” in the world. The “I” should be interpreted in general terms, it is not about artistic testimony pertaining to individual experience, but rather paintings that record the condition of a contemporary everyman. All that is tangible becomes a means to search for order, or to reflect on interpersonal relations. The recurrence of a similar theme in various paintings gives the impression of careful consideration and a calm dialog with the audience.

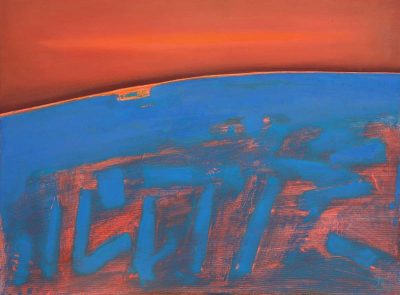

The composition of each piece is very often based on landscape. In the paintings where it constitutes the main motif (Returns. Internal Landscape series) it becomes apparent that the artist seeks metaphysical confirmation in nature. Intriguing frames provide a starting point to build harmonious, non-figurative, open spaces on canvas. It means simplifying the depicted landscapes, stripping them off information noise, until they verge on abstraction. It is as if someone who remains unseen asked the painted motif: what is really important here?

A world seen through narrowed eyes transforms into relationships between spots of color, like in colorist painting, which many of Świgulski’s techniques seem to originate from. A game of contrast, brightness, texture, selection of complementary overtones, elimination of a single color from the palette, a careful arrangement of the planes, in other words, a number of deliberate artistic choices serve not as a means to paint a scenery, but rather to immerse in it. The art’s language is a tool to measure the pulse, the basic rhythm of the landscape. These paintings oscillate between the observation of what is and testing how far that which exists is narratable.

Whether it is the lofty Himalayas or the regular rhythm of furrows in the Polish Jurassic Highland, what really counts is a record of perception so intense that it makes the observer disappear. While walking through the spaces portrayed by Świgulski, one may almost synchronize their breath with that which lasts longer and regardless of human admiration or dislike. In a way, it is a manner of imagining the world without us, or even an attempt at a contemplative departure from the “I” category.

If the features of a landscape provide a kind of framework, figures disrupt its calm stability. Interestingly, silhouettes of people, animals or dreamy images become ontologically equal. The non-figurativeness of these shapes reduced to patches of color delineated from the background with simplified contours, their phantasmagorical nature makes the question of who or what they are irrelevant. It is about the presence. Only in the case of cats (a series by the same title) the purely physical presence – an intriguing mystery of nearly impossible moves and bizarre twists – becomes the main motif. Other shapes, including the dog in The Surroundings series (several consecutive paintings entitled A Family Episode and The Golden Moment), describe relations. The early Self-Portraits with a Shadow are about a difficult relationship man has with the self, a struggle with the dark, the overwhelming. Conversations, in turn, are a record of failed attempts at a dialogue. The inability of two people to communicate is highlighted by a simple solution: each work consists of two separate canvas. Each of the two contains a single, distinct, contrastingly painted figure. While forming an entity, the two also seem to repel one another. Although they share the background and color palette, merging in some of the works into a single two-headed patch, it still makes them appear to be both doomed and fiercely reluctant to suffer each other’s company. These conversations boil down to misunderstandings.

However, what seems to particularly fascinate the artist in recent paintings is intimacy. In line with the title of a series devoted to closeness, all the events centered around a creative effort contribute to it. People’s everyday lives: mornings spent together, when the dog demands to be walked, arguments, moments of intimacy and instants promising an almost metaphysical fulfillment. These last instances somewhat constitute the opposite side of the landscape’s silence. Here, an individual goes beyond the limits of the self, not to disappear in the empty space, but rather to be able to connect with another person (several paintings entitled On the Ellipse of Intimacy, Family Episodes, The Golden Moments). It seems to me that these works oscillate between the two extremes of vital experience. The first one is the epiphanous immersion in the observed nature, the other one – the brief periods when one enters another human’s world. Indeed, one should rather say: other creatures’ world, since there is also a dog which plays such a crucial role in the images of domestic bliss.

Given the chronology of these paintings, ascetic landscapes and deepened intimacy turn out to be the result of many years of searching. The creative process appears to be a fascinating journey during which the artist tests different records of his own experiences and gradually improves the free flow between a busy moment and motionless canvas. He consistently breaks ready-made rationalizations. He rejects what is already known about the depicted situation and aims to immerse in the bare experience, in the kind of existence he faces at a given moment. Once he achieves that state, the creative act becomes synonymous with the act of recovering the sense. It allows one to experience the self more vividly, look around more honestly. It uncovers traces of harmony in the world and interpersonal relations. It exposes or finds them, but doesn’t create them since the starting point of each painting is perpetually that which is perceived, noticed. That which exists.

Jacek Świgulski’s journey leads, therefore, to a conscious artistic choice: the silencing of individual emotions and almost loving trust in the order we form a part of, even though we cannot fully explain or reproduce it. In our clamorous, narcissistic times, it is not necessarily an obvious direction of artistic pursuit.

Agnieszka Skolasińska

translation: Dobrochna Jagiełło

POSTER

VERNISSAGE

1 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

2 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

3 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

4 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

5 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

6 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

7 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

8 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

9 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

10 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

11 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

12 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

13 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

14 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

15 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

16 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

17 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

18 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

19 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

20 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

21 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

22 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

23 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

24 of 24

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05.2025

EXPOSITION

1 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

2 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

3 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

4 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

5 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

6 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

7 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

8 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

9 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

10 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

11 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

12 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

13 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

14 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

15 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

16 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

17 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

18 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

19 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

20 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

21 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

22 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

23 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

24 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

25 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

26 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

27 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

28 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

29 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

30 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

31 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

32 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

33 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

34 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

35 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

36 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

37 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

38 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

39 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

40 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

41 of 41

PŁOCK ART GALLERY, Płock - 23.05/29.06.2025

PAINTINGS

1 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Jura VIII, 2015, oil on the canvas, 54 x 73 cm

2 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Jura VII, 2015, oil on the canvas, 35 x 45 cm

3 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Jura V, 2015, oil on the canvas, 54 x 73 cm

4 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Jura VI, 2015, oil on the canvas, 70 x 90 cm

5 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Jura IX, 2016, oil on the canvas, 90 x 140 cm

6 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Jura IV, 2014, oil on the canvas, 80 x 90 cm

7 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Bieszczady IV, 2015, oil on the canvas, 70 x 90 cm

8 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Bieszczady VI, 2017, oil on the canvas, 80 x 90 cm

9 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Bieszczady XII, 2018, oil on the canvas, 90 x 140 cm

10 of 63

from the RETURNS series, Borów I, 2013, oil on the canvas, 70 x 90 cm

11 of 63

from the RETURNS series, Borów II, 2013, oil on the canvas, 60 x 80 cm

12 of 63

from the RETURNS series, Borów V, 2019, oil on the canvas, 70 x 80 cm

13 of 63

from the RETURNS series, Borów VI, 2019, oil on the canvas, 70 x 80 cm

14 of 63

from the RETURNS series, Borów VII, 2020, oil on the canvas, 71 x 91 cm

15 of 63

from the RETURNS series, Chang La I, 2019, oil on the canvas, 95 x 120 cm

16 of 63

from the RETURNS series, Chang La II, 2019, oil on the canvas, 95 x 120 cm

17 of 63

from the RETURNS series, Chang La IV, 2020, oil on the canvas, 95 x 120 cm

18 of 63

from the RETURNS series, SIMPLE SEA VIEW I, 2023, oil on the canvas, 70 x 90 cm

19 of 63

from the RETURNS series, SIMPLE SEA VIEW II, 2023, oil on the canvas, 70 x 90 cm

20 of 63

From the RETURNS series, Interplay I, INDUSTRIAL LODZ, 2023, oil on the canvas, 80 x 80 cm

21 of 63

from the RETURNS series, HAVEN I, 2014, oil on the canvas, 50 x 70 cm

22 of 63

from the RETURNS series, HAVEN II, 2014, oil on the canvas, 80 x 90 cm

23 of 63

from the RETURNS series, HAVEN III, 2019, oil on the canvas, 54 x 73 cm

24 of 63

from the RETURNS series, HAVEN IV, 2019, oil on the canvas, 54 x 73 cm

25 of 63

from the RETURNS series, HAVEN IX, 2024, oil on the canvas, 95 x 120 cm

26 of 63

from the RETURNS series, HAVEN V, 2020, oil on the canvas, 71 x 91 cm

27 of 63

from the RETURNS series, HAVEN VI, 2021, oil on the canvas, 90 x 140 cm

28 of 63

from the RETURNS series, HAVEN VII, 2021, oil on the canvas, 90 x 140 cm

29 of 63

from the RETURNS series, HAVEN VIII, 2024, oil on the canvas, 95 x 120 cm

30 of 63

A FAMILY EPISODE I, 2019, oil on the canvas, 146 x 110 cm

31 of 63

A FAMILY EPISODE II, 2019, oil on the canvas, 105 x 150 cm

32 of 63

A FAMILY EPISODE III, 2019, oil on the canvas, 150 x 105 cm

33 of 63

MEDITAION IN BLUE, 2017, oil on the canvas 141 x 110 cm

34 of 63

PRAYER IN THE GREEN, 2016, oil on the canvas, 100 x 150 cm

35 of 63

THE AFTERNOON CLASH, III, 2023, oil on the canvas, 100 x 100 cm

36 of 63

THE AFTERNOON CLASH, IV, 2023, oil on the canvas, 100 x 100 cm

37 of 63

THE PINK CONFESSION, 2016, oil on the canvas, 110 x 145 cm

38 of 63

THE SURROUNDINGS, 2016, oil on the canvas, 104 x 151 cm

39 of 63

EXPECTANCY, 2017, oil on the canvas, 120 x 90 cm

40 of 63

THE GOLDEN MOMENT I, 2022, oil on the canvas,105 x 150 cm

41 of 63

THE GOLDEN MOMENT II, 2022, oil on the canvas,105 x 150 cm

42 of 63

THE GOLDEN MOMENT III, 2022, oil on the canvas,105 x 150 cm

43 of 63

A LIFE THAT DIDN’T HAPPEN, 2016, oil on the canvas, 104 x 150 cm

44 of 63

CAT I, 2013, oil on the canvas, 50 x 70 cm

45 of 63

CAT II, 2013, oil on the canvas, 50 x 60 cm

46 of 63

CAT III, 2013, oil on the canvas, 54 x 65 cm

47 of 63

CAT IX, 2014, oil on the canvas, 47 x 65 cm

48 of 63

CAT V, 2013, oil on the canvas, 45 x 50 cm

49 of 63

CAT VI, 2013, oil on the canvas, 41 x 27 cm

50 of 63

CAT VII, 2013, oil on the canvas, 35 x 45 cm

51 of 63

CAT VIII, 2014, oil on the canvas, 50 x 65 cm

52 of 63

CAT X, 2014, oil on the canvas, 50 x 60 cm

53 of 63

CAT XI, 2014, oil on the canvas, 65 x 47 cm

54 of 63

CONVERSATION I, 2009, oil on the canvas, 90 x 90 cm

55 of 63

CONVERSATION II, 2009, oil on the canvas, 90 x 90 cm

56 of 63

CONVERSATION III, 2009, oil on the canvas, 90 x 90 cm

57 of 63

CONVERSATION IV, 2009, oil on the canvas, 90 x 90 cm

58 of 63

CONVERSATION V, 2009, oil on the canvas, 90 x 100 cm

59 of 63

CONVERSATION VI, 2009, oil on the canvas, 90 x 100 cm

60 of 63

SELF-PORTRAIT WITH A SHADOW I, 2006, oil on the canvas, 90 x 110 cm

61 of 63

SELF-PORTRAIT WITH A SHADOW III, 2006, oil on the canvas, 85 x 100 cm

62 of 63

SELF-PORTRAIT WITH A SHADOW IV, 2006, oil on the canvas, 100 x 120 cm

63 of 63

SELF-PORTRAIT WITH A SHADOW VI, 2006, oil on the canvas, 100 x 110 cm